Left-Hand Walking

By: Heather DeRome, with thanks to Frank Koonce.

As is necessary in a piece of monumental proportions, after Bach has arrived back to the home-key, there needs be a little time for winding down. These sections can vary greatly in length; in the C-major fugue, BWV 1005, for example, that section takes 110 measures, but in this piece, Bach only uses eight. Typically, and as is the case here, the writing gives the performer a chance for a show of bravura.

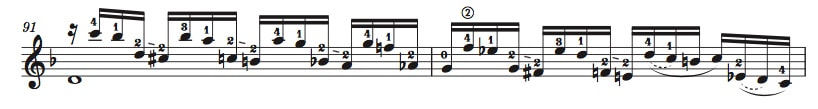

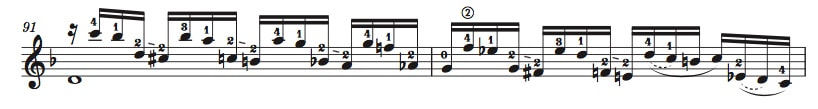

When Frank and I were arranging this, and when he first sent me his suggested fingerings for mm 91-92, I answered that I found it difficult to do all those shifts.

His response: “Don't shift; walk.” Similarly, when teaching this piece, my students invariably would trip over that fingering, until I showed them how to use it properly: You cross finger 2 over finger 1 (so that both fingers are momentarily on the same fret), by “walking” on 1. Then you shift with 2 (as shown by the guide-finger dash). This way, you do not have back-to-back shifts. For example in the second group of sixteenths, when playing the last two notes, A and C, do not shift between the A and C. Instead, after playing A, cross 2 over 1, having both fingers momentarily on the fifth fret, and then shift from C down to B (see the video for a hands on explanation).

Now, I may be biased about Frank because he is a friend and colleague, but I think the world of him, and I don’t think there are many people out there who understand the hands as well as he does ––especially the left hand. In one of our newsletters, I wrote about how it seemed like Frank sometimes had X-ray vision, because he can tell exactly how someone is using their hand or even how they are hearing (or missing) the counterpoint, simply by looking at a score with their fingerings.

In the first few weeks that we were working on the scores (we began with the Chaconne), there were times when I would say “I don’t like that jump” and he’d answer: “Don’t jump; walk.”

I asked Frank if he would explain this more clearly, and here was his answer, copied from an old email:

Frank:

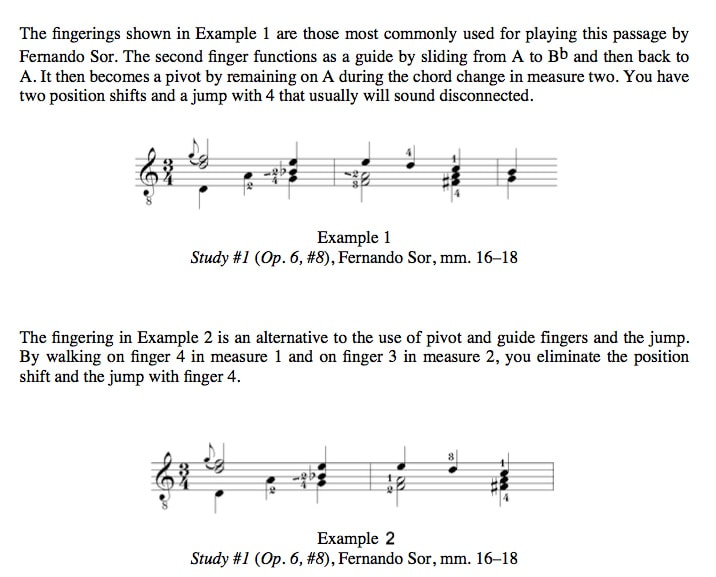

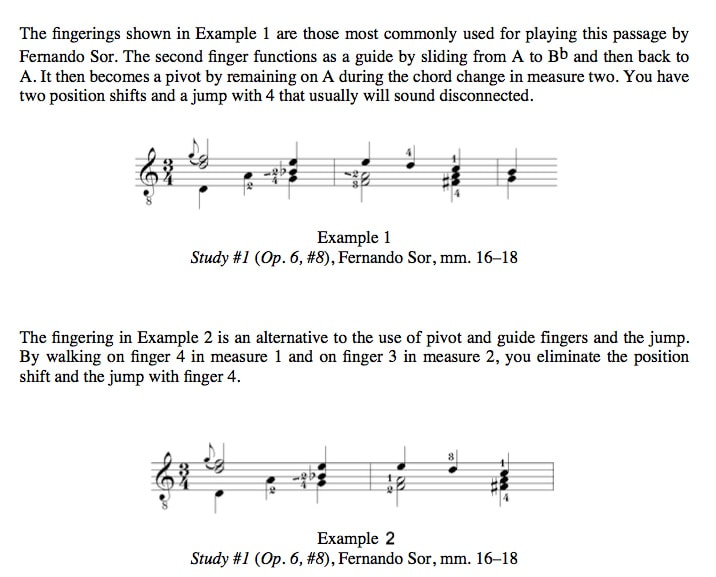

See the attachment. Example 1 is jumping; example 2 is walking.

In example 1, from the last note of the first measure to the first beat of the second, there is no intervening note on which to walk (alternate fingers). Your only recourse with this fingering, is to jump the fourth finger across a string in one movement. In example 2, which you yourself suggested, you walk on 4 (as though you are making a step) to different fingers that are used for the following chord. Because 4 is attached, it supports the hand and provides a reference point to judge the distance when walking to the other fingers. It is like walking upstairs instead of running upstairs. When you walk, with one foot remaining on the ground, you know exactly how far to step. When running, however, both feet come off the ground, and you can easily lose your perspective of where you are, and then you may stumble.

To further explain, here is an excerpt from “Left-Hand movement: A Bag of Tricks,” an article by Frank that can be viewed on his website at: https://www.frankkoonce.com/articles/A%20Bag%20of%20Tricks.pdf

Back to his email response to me:

Frank:

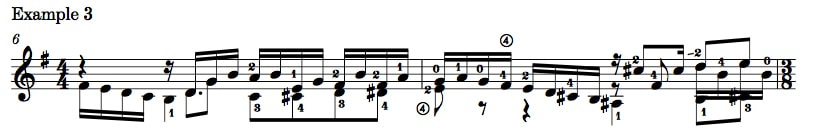

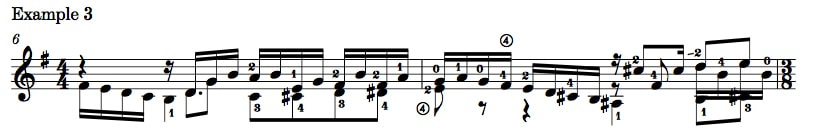

I also think most guitarists over-use guide fingers in places where walking would be better (as just shown in the article above). In example 3 below, from the Allemande of BWV 996, I don't slide (or jump) with 2 from the last beat of measure 7 to the downbeat of measure 8 as many would do. Instead, I transfer the weight of my hand to 1, the last A in measure 7 (like from one foot to another), and I walk on 1 to move 2 to the E in measure 8.

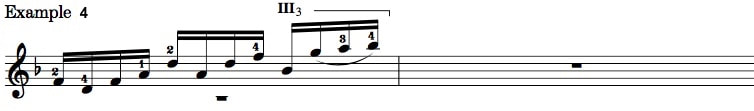

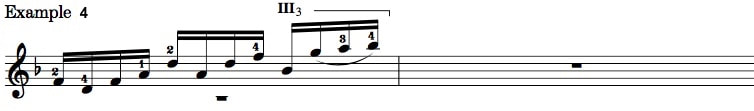

Similarly, in example 4, at measure 53 of the Ciaccona, you can keep all the fingers down for the d minor chord on beat one, but, while or just after after you play the A, you relax 2 and 4 and walk on 1 (as though you are making a step) to move 2 to the second string. Because 1 is attached, it supports the hand and provides a reference point to judge the distance when walking to the second string.

I hope these examples and explanations help.

With best wishes,

Frank

Frank and I worked and RE-worked the fingerings in the book. We have played the fingerings ourselves and have also given them to our students, and made changes whenever there was a fingering that did not work for a wide range of players. All this notwithstanding, I realize that I am predisposed to being partisan to the fingerings in our book; on the other hand, I know there is always room for refinement. Still, I’d like to suggest that if a fingering seems odd or awkward to you––ESPECIALLY if it feels odd or awkward––before changing it to something else, please try to understand our possible musical and/or technical reasons for choosing that fingering. It may be there to allow a voice to sustain, or to support the phrasing implied by Bach’s slur. It may require you to use your hand in a more relaxed manner, as our little email exchange shows. Being an advanced player does not simply mean that one can play difficult things; it means that he or she has found ways to use the hands so that things are no longer difficult. If there is a fingering you are not sure about, please ask. Part of the reason for this website is to help players and teachers with these kinds of concerns, and for musicians to learn from each other.

Please see the video, part-four, linked on the right, which discusses only the closing section of the G-minor Fuga, and gives some helpful tips about how to use the suggested fingerings in our edition.

Copyright Koonce/DeRome, 2019. All rights reserved

When Frank and I were arranging this, and when he first sent me his suggested fingerings for mm 91-92, I answered that I found it difficult to do all those shifts.

His response: “Don't shift; walk.” Similarly, when teaching this piece, my students invariably would trip over that fingering, until I showed them how to use it properly: You cross finger 2 over finger 1 (so that both fingers are momentarily on the same fret), by “walking” on 1. Then you shift with 2 (as shown by the guide-finger dash). This way, you do not have back-to-back shifts. For example in the second group of sixteenths, when playing the last two notes, A and C, do not shift between the A and C. Instead, after playing A, cross 2 over 1, having both fingers momentarily on the fifth fret, and then shift from C down to B (see the video for a hands on explanation).

Now, I may be biased about Frank because he is a friend and colleague, but I think the world of him, and I don’t think there are many people out there who understand the hands as well as he does ––especially the left hand. In one of our newsletters, I wrote about how it seemed like Frank sometimes had X-ray vision, because he can tell exactly how someone is using their hand or even how they are hearing (or missing) the counterpoint, simply by looking at a score with their fingerings.

In the first few weeks that we were working on the scores (we began with the Chaconne), there were times when I would say “I don’t like that jump” and he’d answer: “Don’t jump; walk.”

I asked Frank if he would explain this more clearly, and here was his answer, copied from an old email:

Frank:

See the attachment. Example 1 is jumping; example 2 is walking.

In example 1, from the last note of the first measure to the first beat of the second, there is no intervening note on which to walk (alternate fingers). Your only recourse with this fingering, is to jump the fourth finger across a string in one movement. In example 2, which you yourself suggested, you walk on 4 (as though you are making a step) to different fingers that are used for the following chord. Because 4 is attached, it supports the hand and provides a reference point to judge the distance when walking to the other fingers. It is like walking upstairs instead of running upstairs. When you walk, with one foot remaining on the ground, you know exactly how far to step. When running, however, both feet come off the ground, and you can easily lose your perspective of where you are, and then you may stumble.

To further explain, here is an excerpt from “Left-Hand movement: A Bag of Tricks,” an article by Frank that can be viewed on his website at: https://www.frankkoonce.com/articles/A%20Bag%20of%20Tricks.pdf

Back to his email response to me:

Frank:

I also think most guitarists over-use guide fingers in places where walking would be better (as just shown in the article above). In example 3 below, from the Allemande of BWV 996, I don't slide (or jump) with 2 from the last beat of measure 7 to the downbeat of measure 8 as many would do. Instead, I transfer the weight of my hand to 1, the last A in measure 7 (like from one foot to another), and I walk on 1 to move 2 to the E in measure 8.

Similarly, in example 4, at measure 53 of the Ciaccona, you can keep all the fingers down for the d minor chord on beat one, but, while or just after after you play the A, you relax 2 and 4 and walk on 1 (as though you are making a step) to move 2 to the second string. Because 1 is attached, it supports the hand and provides a reference point to judge the distance when walking to the second string.

I hope these examples and explanations help.

With best wishes,

Frank

Frank and I worked and RE-worked the fingerings in the book. We have played the fingerings ourselves and have also given them to our students, and made changes whenever there was a fingering that did not work for a wide range of players. All this notwithstanding, I realize that I am predisposed to being partisan to the fingerings in our book; on the other hand, I know there is always room for refinement. Still, I’d like to suggest that if a fingering seems odd or awkward to you––ESPECIALLY if it feels odd or awkward––before changing it to something else, please try to understand our possible musical and/or technical reasons for choosing that fingering. It may be there to allow a voice to sustain, or to support the phrasing implied by Bach’s slur. It may require you to use your hand in a more relaxed manner, as our little email exchange shows. Being an advanced player does not simply mean that one can play difficult things; it means that he or she has found ways to use the hands so that things are no longer difficult. If there is a fingering you are not sure about, please ask. Part of the reason for this website is to help players and teachers with these kinds of concerns, and for musicians to learn from each other.

Please see the video, part-four, linked on the right, which discusses only the closing section of the G-minor Fuga, and gives some helpful tips about how to use the suggested fingerings in our edition.

Copyright Koonce/DeRome, 2019. All rights reserved

Videos

Videos Articles

Articles Left-Hand Walking

Left-Hand Walking