Compound-Melodic Notation

By: Frank Koonce and Heather DeRome

“Compound melody” is a style of composition in which two or more voices may be derived from what appears on paper to be a single voice. This is the notation Bach used in writing his solo violin works as well as his cello works. Another term that is sometimes used for this is “implied polyphony.” Compound-melodic notation is like musical shorthand that greatly reduces the clutter of rests, ties, and separate stems and beams that would be required in polyphonic notation. This is especially helpful for music written on a single staff, such as the violin and cello works. An inherent limitation of this notation, however, is that the specific voice to which a note belongs is sometimes unclear. Consequently, it becomes the responsibility of the player to determine the interplay of voices. Notwithstanding, a “silver lining” is that it can also result in different interpretations, which keeps the music fresh and challenging to performers.

To understand how to extract polyphony from a compound melody, it is helpful to study examples taken from Bach’s own lute and keyboard arrangements of works that he originally wrote for the violin or cello. For instance, the second violin Sonata, BWV 1003, exists in a version for the keyboard, BWV 964. Example 1a, from the third movement of the violin version, illustrates the limitations of notating the upper two voices mostly as a compound melody, compared to the fully polyphonic notation of 1b, from the keyboard version (transposed to match the violin key).

Example 1: Sonata 2, Andante, mm. 3–4 (a) for violin; (b) for keyboard.

In compound-melodic notation, as may be seen when comparing the violin notation to that of the keyboard, larger intervals within what otherwise is a stepwise line may suggest the presence of a second melody, or of rudimentary structures for harmonic and bass support.

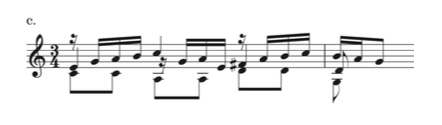

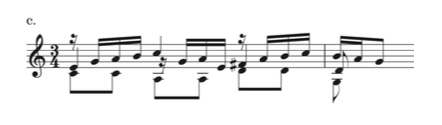

Example 1c shows a compromise for the guitar, in single-staff notation, that still allows the overlapping of notes to distinguish the different voices.

Bach’s notation for the violin is mostly in compound-melodic notation although it sometimes changes to polyphony for enhanced clarity when the voicing is more complex (as in the fugues). Individual voices in music such as this rely on their interaction with other voices to sound complete, and would often appear only as melodic fragments in polyphonic notation. A comparison of Example 2 a with b and c shows how the amalgamation of voices prevents these fragments from seeming more rhythmically intricate than they are aurally perceived.

Also, as in spoken word in which an orator may choose different rhetorical devices to effectively communicate or persuade, a musician can group notes in various ways to convey nuanced expressions or for selective emphasis. Thus, compound-melodic notation gives the performer more latitude in how to sustain and overlap notes, to “realize” or bring out voices so they are perceptible to the listener.

Example 2: Partita 2, Allemanda, mm. 1–2 (a) Bach’s original compound-melodic notation for the violin; (b) and (c) two of many possible realizations, rewritten as two-voice polyphony.

In Example 2c, measure 2, the E on beat three and the C-sharp on the second half of beat four, shown in brackets, are possible notes to add if more developed and fully independent voice lines are desired.

A discerning musician can make his or her own choices, according to personal taste. There is no one “right” answer, but writing the music in polyphonic notation and committing to a decision serves as an illuminating exercise. This process unveils the rich variety of ways the music can be experienced and interpreted.

The above example also shows the problems of artificially imposing a standard two-voice texture onto what is essentially a completely different approach to the very art of composition. In our guitar arrangements, we followed Bach’s practice of mainly writing in compound-melodic notation because we did not want to irrevocably assign subjective decisions that are best left to individual players. We switched to polyphonic notation only when a technical adaptation for the guitar seemed to justify the change (such as shown in Example 1c). We did, however, recommend fingerings that would allow the multi-voice texture of the music to be apparent.

To understand how to extract polyphony from a compound melody, it is helpful to study examples taken from Bach’s own lute and keyboard arrangements of works that he originally wrote for the violin or cello. For instance, the second violin Sonata, BWV 1003, exists in a version for the keyboard, BWV 964. Example 1a, from the third movement of the violin version, illustrates the limitations of notating the upper two voices mostly as a compound melody, compared to the fully polyphonic notation of 1b, from the keyboard version (transposed to match the violin key).

Example 1: Sonata 2, Andante, mm. 3–4 (a) for violin; (b) for keyboard.

In compound-melodic notation, as may be seen when comparing the violin notation to that of the keyboard, larger intervals within what otherwise is a stepwise line may suggest the presence of a second melody, or of rudimentary structures for harmonic and bass support.

Example 1c shows a compromise for the guitar, in single-staff notation, that still allows the overlapping of notes to distinguish the different voices.

Bach’s notation for the violin is mostly in compound-melodic notation although it sometimes changes to polyphony for enhanced clarity when the voicing is more complex (as in the fugues). Individual voices in music such as this rely on their interaction with other voices to sound complete, and would often appear only as melodic fragments in polyphonic notation. A comparison of Example 2 a with b and c shows how the amalgamation of voices prevents these fragments from seeming more rhythmically intricate than they are aurally perceived.

Also, as in spoken word in which an orator may choose different rhetorical devices to effectively communicate or persuade, a musician can group notes in various ways to convey nuanced expressions or for selective emphasis. Thus, compound-melodic notation gives the performer more latitude in how to sustain and overlap notes, to “realize” or bring out voices so they are perceptible to the listener.

Example 2: Partita 2, Allemanda, mm. 1–2 (a) Bach’s original compound-melodic notation for the violin; (b) and (c) two of many possible realizations, rewritten as two-voice polyphony.

In Example 2c, measure 2, the E on beat three and the C-sharp on the second half of beat four, shown in brackets, are possible notes to add if more developed and fully independent voice lines are desired.

A discerning musician can make his or her own choices, according to personal taste. There is no one “right” answer, but writing the music in polyphonic notation and committing to a decision serves as an illuminating exercise. This process unveils the rich variety of ways the music can be experienced and interpreted.

The above example also shows the problems of artificially imposing a standard two-voice texture onto what is essentially a completely different approach to the very art of composition. In our guitar arrangements, we followed Bach’s practice of mainly writing in compound-melodic notation because we did not want to irrevocably assign subjective decisions that are best left to individual players. We switched to polyphonic notation only when a technical adaptation for the guitar seemed to justify the change (such as shown in Example 1c). We did, however, recommend fingerings that would allow the multi-voice texture of the music to be apparent.